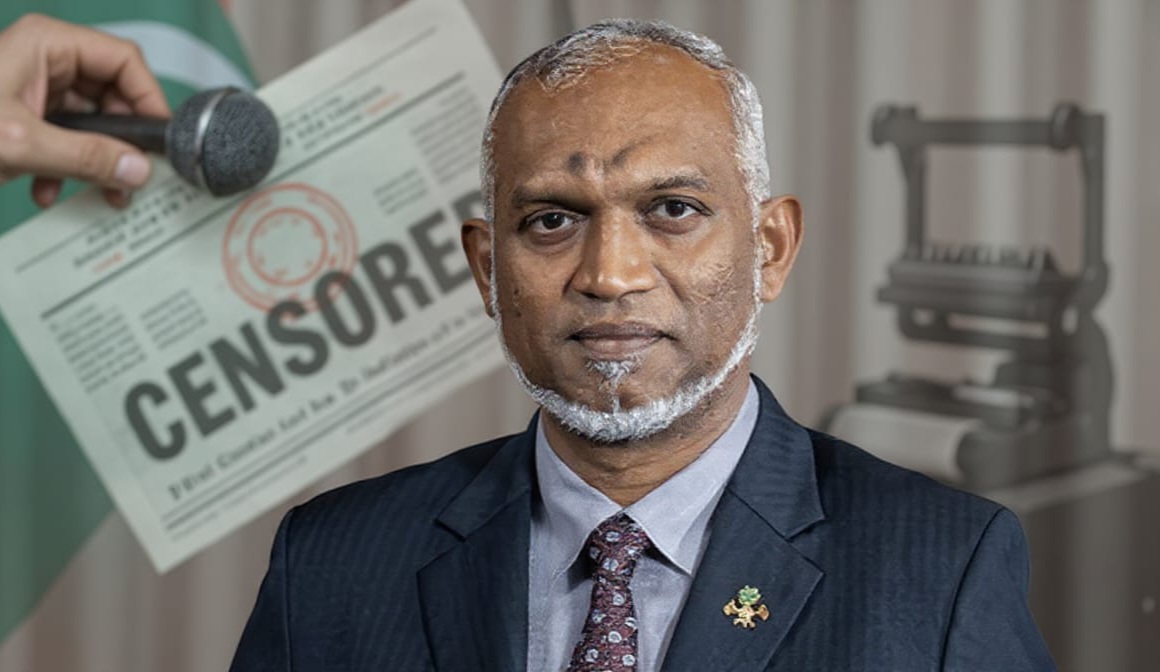

In a calculated move to curb press freedom, President Dr. Mohamed Muizzu’s administration introduced a sweeping media regulation bill to the People’s Majlis on August 19, 2025, tabled by MP Abdul Hannan Aboobakuru. Framed as a defense of religious values and ethical journalism, the legislation is widely condemned as a pretext to silence reports on rampant government corruption, wielding vague terms like “fake news” and “national interest” to suppress dissent. With the People’s Majlis dominated by Muizzu’s People’s National Congress (PNC), now holding a supermajority of 75 out of 93 seats after independent members joined post-election, MPs serve as loyal proxies for the executive, rubber-stamping policies that threaten the fourth estate—the media’s vital role in democratic accountability. This bill, empowering a new commission with punitive authority, marks a dangerous step toward autocratic control in a nation long shaped by struggles for sovereignty yet now plagued by corruption and democratic erosion.

The proposed legislation establishes the Maldives Media and Broadcasting Commission, dissolving the existing Maldives Media Council and Broadcasting Commission. The commission’s seven-member board comprises three members appointed directly by the President, subject to approval by the PNC-dominated People’s Majlis, and four elected by registered media outlets with voting restricted to journalists from outlets active for at least five years. The commission’s president, also a presidential nominee approved by the loyalist-parliament, cements executive dominance—a stark contrast to balanced appointment processes in Western democracies.

The commission wields sweeping powers: ordering content corrections, issuing warnings, imposing fines up to 10% of a media outlet’s previous year’s revenue, suspending broadcasts, or revoking licenses through court orders. Non-compliance incurs fines of MVR 5,000 to MVR 100,000. Vaguely defined offenses, such as “fake news,” content “undermining national interest,” or material deemed “inappropriate” under religious pretexts like Islam’s prohibition on lying, invite abuse against critical voices. The commission can also summon witnesses, collect evidence, and order authorities to shut down platforms spreading disinformation.

All media outlets, including newspapers and broadcasters, must register with the commission to operate legally. A temporary five-member committee, appointed by the Civil Service Commission, will oversee the transition. With the People’s Majlis functioning as a subservient legislature, approval of presidential appointees is a formality, eroding checks and balances.

The bill emerges amid pervasive corruption, including embezzlement and nepotism, which have drawn intense scrutiny. This corruption thrives alongside democratic backsliding. Classified as “Partly Free” in 2025, the Maldives is experiencing “autocratization.” The PNC’s supermajority, solidified in April 2024 and expanded to 75 seats as independents aligned with Muizzu, enables reforms with minimal opposition, with MPs acting as loyalists rather than independent representatives. Already judicial independence has been compromised. The media bill’s reliance on a compliant People’s Majlis to approve presidential appointees ensures the commission will likely serve as a regime tool, not an impartial regulator.

The government’s efforts to eliminate independent media have drawn widespread criticism from democracy advocates, who argue the bill is designed to eradicate free journalism. The Maldives Media Council (MMC) warned that the bill opens the door for penalizing media outlets without any fairness, stating, “The bill opens the door for penalizing media outlets without any fairness, giving the power to this newly created commission to shut down a media outlet even before a case is proven through the judicial system.” Similarly, the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA), which works to protect journalists’ rights, condemned the bill as a tool to bring media under the President’s control, declaring, “This association believes that the bill is designed with the philosophy of concentrating significant regulatory powers over media in the President’s hands, bringing media outlets under complete government control, and keeping journalists in a state of fear.”

Opposition leaders have been vocal. Former President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih called for the withdrawal of the bill, describing it as an attack on journalism that imposes hefty fines on media outlets and journalists and allows for the revocation of newspaper registrations. Fayyaz Ismail, chairperson of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), called the bill a deliberate plan by Muizzu to eliminate independent media, stating, “The Media Regulation Bill is a plan devised by Muizzu to eliminate independent media from the Maldives. Media is the backbone of a democracy. The proposed bill will strip away the protection for journalists and media outlets, giving direct control to the President through the regulatory commission.” He warned that the government’s actions risk returning the Maldives to an era where revealing the truth was a punishable offense, adding, “We cannot go back to an era where revealing the truth was a punishable offense.”

MDP President and former Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid echoed these concerns, labeling the bill a step toward authoritarianism. “Regulating journalism through members appointed by the President, with a chairperson appointed by the President, is another step taken by this government to eliminate free journalism,” Shahid said. He urged journalists and People’s Majlis members to resist, stating, “One of the most fundamental characteristics of an authoritarian regime is the elimination of free journalism, keeping journalists in constant fear and unease. I call upon all journalists and honorable members of the People’s Majlis not to allow this government the opportunity to take away the freedom of Maldivian journalism, which has come this far through many sacrifices.”

Journalists staged silent protests at the People’s Majlis, prompting debate to be deferred to the next term, signaling potential revisions under pressure.

This bill represents a grave assault on the Maldives’ fourth estate. In a nation gripped by corruption and autocratic drift, where a loyalist-parliament enables unchecked executive power, the proposed commission risks turning media into a state mouthpiece. Unlike Western safeguards, the Maldives’ system lacks transparency and independence, allowing Muizzu to silence critical voices under the guise of ethics. The media’s role in exposing graft and ensuring accountability is vital—yet this bill threatens to smother it. Domestic protests and international pressure may force a rethink, but without robust reforms, the Maldives risks sliding deeper into autocracy, with a free press as its first casualty.

The proposed legislation establishes the Maldives Media and Broadcasting Commission, dissolving the existing Maldives Media Council and Broadcasting Commission. The commission’s seven-member board comprises three members appointed directly by the President, subject to approval by the PNC-dominated People’s Majlis, and four elected by registered media outlets with voting restricted to journalists from outlets active for at least five years. The commission’s president, also a presidential nominee approved by the loyalist-parliament, cements executive dominance—a stark contrast to balanced appointment processes in Western democracies.

The commission wields sweeping powers: ordering content corrections, issuing warnings, imposing fines up to 10% of a media outlet’s previous year’s revenue, suspending broadcasts, or revoking licenses through court orders. Non-compliance incurs fines of MVR 5,000 to MVR 100,000. Vaguely defined offenses, such as “fake news,” content “undermining national interest,” or material deemed “inappropriate” under religious pretexts like Islam’s prohibition on lying, invite abuse against critical voices. The commission can also summon witnesses, collect evidence, and order authorities to shut down platforms spreading disinformation.

All media outlets, including newspapers and broadcasters, must register with the commission to operate legally. A temporary five-member committee, appointed by the Civil Service Commission, will oversee the transition. With the People’s Majlis functioning as a subservient legislature, approval of presidential appointees is a formality, eroding checks and balances.

The bill emerges amid pervasive corruption, including embezzlement and nepotism, which have drawn intense scrutiny. This corruption thrives alongside democratic backsliding. Classified as “Partly Free” in 2025, the Maldives is experiencing “autocratization.” The PNC’s supermajority, solidified in April 2024 and expanded to 75 seats as independents aligned with Muizzu, enables reforms with minimal opposition, with MPs acting as loyalists rather than independent representatives. Already judicial independence has been compromised. The media bill’s reliance on a compliant People’s Majlis to approve presidential appointees ensures the commission will likely serve as a regime tool, not an impartial regulator.

The government’s efforts to eliminate independent media have drawn widespread criticism from democracy advocates, who argue the bill is designed to eradicate free journalism. The Maldives Media Council (MMC) warned that the bill opens the door for penalizing media outlets without any fairness, stating, “The bill opens the door for penalizing media outlets without any fairness, giving the power to this newly created commission to shut down a media outlet even before a case is proven through the judicial system.” Similarly, the Maldives Journalists Association (MJA), which works to protect journalists’ rights, condemned the bill as a tool to bring media under the President’s control, declaring, “This association believes that the bill is designed with the philosophy of concentrating significant regulatory powers over media in the President’s hands, bringing media outlets under complete government control, and keeping journalists in a state of fear.”

Opposition leaders have been vocal. Former President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih called for the withdrawal of the bill, describing it as an attack on journalism that imposes hefty fines on media outlets and journalists and allows for the revocation of newspaper registrations. Fayyaz Ismail, chairperson of the Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), called the bill a deliberate plan by Muizzu to eliminate independent media, stating, “The Media Regulation Bill is a plan devised by Muizzu to eliminate independent media from the Maldives. Media is the backbone of a democracy. The proposed bill will strip away the protection for journalists and media outlets, giving direct control to the President through the regulatory commission.” He warned that the government’s actions risk returning the Maldives to an era where revealing the truth was a punishable offense, adding, “We cannot go back to an era where revealing the truth was a punishable offense.”

MDP President and former Foreign Minister Abdulla Shahid echoed these concerns, labeling the bill a step toward authoritarianism. “Regulating journalism through members appointed by the President, with a chairperson appointed by the President, is another step taken by this government to eliminate free journalism,” Shahid said. He urged journalists and People’s Majlis members to resist, stating, “One of the most fundamental characteristics of an authoritarian regime is the elimination of free journalism, keeping journalists in constant fear and unease. I call upon all journalists and honorable members of the People’s Majlis not to allow this government the opportunity to take away the freedom of Maldivian journalism, which has come this far through many sacrifices.”

Journalists staged silent protests at the People’s Majlis, prompting debate to be deferred to the next term, signaling potential revisions under pressure.

This bill represents a grave assault on the Maldives’ fourth estate. In a nation gripped by corruption and autocratic drift, where a loyalist-parliament enables unchecked executive power, the proposed commission risks turning media into a state mouthpiece. Unlike Western safeguards, the Maldives’ system lacks transparency and independence, allowing Muizzu to silence critical voices under the guise of ethics. The media’s role in exposing graft and ensuring accountability is vital—yet this bill threatens to smother it. Domestic protests and international pressure may force a rethink, but without robust reforms, the Maldives risks sliding deeper into autocracy, with a free press as its first casualty.