The coco de mer (Lodoicea maldivica), known as the sea coconut, double coconut, or Maldive coconut, is a botanical marvel renowned for producing the largest seed in the plant kingdom, weighing up to 36 kg. Endemic to the Seychelles islands of Praslin and Curieuse, this palm’s historical and cultural ties to the Maldives reveal a fascinating story of maritime exploration, myth-making, and scientific discovery. The Maldives, an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, played a pivotal role in introducing the coco de mer to the world, shaping its name and early lore. This article explores the Maldivian connection to the coco de mer, the origins of its scientific name Lodoicea maldivica, and the cultural traditions that linked it to the sea, with references to historical documents.

The Maldivian Connection: A Gift from the Sea

Long before the coco de mer’s true origin was identified, its massive, bilobed seeds washed ashore on the beaches of the Maldives, carried eastward by Indian Ocean currents. These seeds, hollow after germination, floated vast distances from the Seychelles, appearing as mysterious objects to Maldivian islanders. Lacking knowledge of their terrestrial source, Maldivians crafted myths, believing the seeds grew on a mythical tree at the bottom of the sea, a gift from the Sea King. In the Maldives, the coco de mer was locally known as Thaavah Kaarhi, and it held significant cultural and medicinal value. The seeds were considered symbols of good fortune, and their hard shells were used in traditional medicine, particularly for sexual enhancement and as a supposed antidote to poisoning.

Maldivians were the first to trade these seeds, introducing them to the broader Indian Ocean world. By the 16th century, the coco de mer had become a prized commodity, valued for its rarity and exotic appearance. European sailors and traders encountered the seeds through Maldivian intermediaries, who collected them from their shores. The seeds’ suggestive shape fueled romantic and mystical tales, with Maldivian legends portraying them as the “forbidden fruit” associated with love and passion. This trade elevated the coco de mer’s status, with polished shells adorned with jewels becoming collectibles in European noble galleries.

The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (Volume 19, 1910) provides insight into this early connection. It notes that the coco de mer was “well-known to the natives of the Maldives,” who regarded it as a marine product due to its frequent appearance on their beaches. The journal highlights the Maldives’ role in disseminating the seed, stating that “the nuts were carried by ocean currents to the Maldives, where they were gathered and traded as objects of curiosity and value.” This document underscores the Maldivians’ role in introducing the coco de mer to global trade networks, long before its botanical origin was understood.

The Myth of the Sea Coconut and the Name “Coco de Mer”

The name “coco de mer” (French for “coconut of the sea”) directly stems from Maldivian tradition and the maritime mystery surrounding the seed. Early European explorers, encountering the seeds through Maldivian trade, adopted the local belief that they originated from an underwater tree.

This misconception persisted until 1768, when French explorer Chevalier Marion Dufresne landed in the Seychelles and identified the coco de mer as the fruit of a terrestrial palm. Prior to this discovery, the seed’s appearance in the Maldives fueled speculation, with some believing it was a sea-bean or drift seed. The Maldivian tradition of attributing the seed to a mythical underwater tree shaped early European perceptions, cementing the name coco de mer in botanical and cultural lexicon.

bThe Scientific Name: Lodoicea maldivica and Its Maldivian Roots

Lodoicea Maldivica was first recorded by Garcia de Orta in 1563 as coco das Maldivas. The scientific name Lodoicea maldivica further reflects the Maldives’ historical association with the coco de mer. The genus name Lodoicea is attributed to Philibert Commerson, who may have derived it from Lodoicus, a Latinized form of Louis, in honor of King Louis XV of France, or possibly from Laodice, a figure from Greek mythology. The specific epithet maldivica directly references the Maldives, where the seeds were first encountered and traded. This name was formalized before the 18th century, when the Seychelles were uninhabited, and the seeds’ true origin was unknown.

In 1750, Dutch botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius studied the seed and named it Cocus maldivica, reinforcing the Maldivian connection. However, in 1801, French botanist J.J. de La Billardière proposed Lodoicea seychellarum, a name more geographically accurate to its Seychelles origin. Despite this, the earlier name Lodoicea maldivica took precedence under international botanical nomenclature conventions in 1917, prioritizing older names. Thus, the scientific name Lodoicea maldivica preserves the Maldives’ historical role, even though the palm is not native to the archipelago.

The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (1910) supports this naming history, noting that “the specific name maldivica was given due to the frequent drift of the nuts to the Maldives, where they were first known to science.” It further mentions that early botanists, unaware of the Seychelles’ palm, relied on Maldivian accounts and specimens, solidifying the name’s connection to the Maldives.

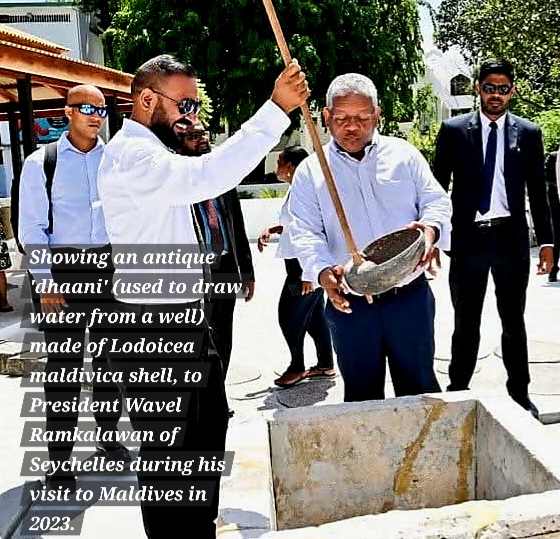

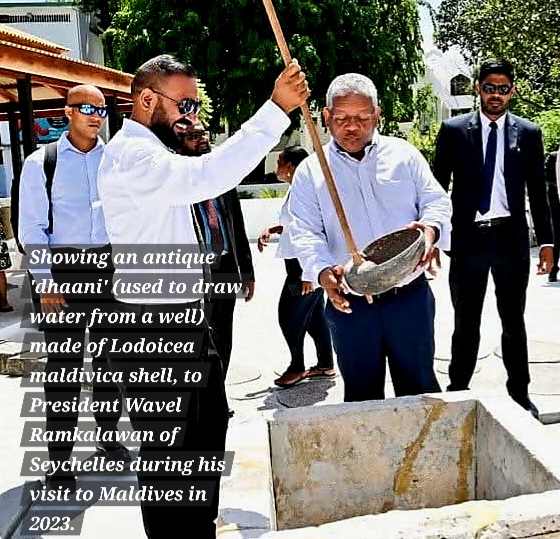

Cultural and Historical Significance in the Maldives

In Maldivian culture, the coco de mer was more than a trade item; it was a symbol of mystique and utility. The hard shells were crafted into goblets, often engraved with gold or silver, used by Indian rajahs to neutralize toxins, a belief rooted in Maldivian medicinal practices. The seeds’ rarity made them a status symbol, and their trade enriched Maldivian communities. During the era of Maldivian Sultans, embassies sent to foreign kings always included coco de mer among the gifts. Copies of missives from the Sultan of the Maldives to the Dutch and later British Governors of Ceylon mention the inclusion of coco de mer in these diplomatic offerings, highlighting its value in fostering alliances. The Maldives’ strategic position in Indian Ocean trade routes facilitated the coco de mer’s spread, introducing it to Arab, Indian, and later European markets.The Journal also alludes to the cultural significance, describing how “Maldivian islanders revered the nut as of divine origin, incorporating it into their traditional pharmacopeia.” This reverence underscores the Maldives’ role in elevating the coco de mer’s global profile, transforming it from a beachcomber’s find into a coveted artifact.

Conclusion

The coco de mer’s connection to the Maldives is a testament to the power of human curiosity and maritime exchange. Maldivians, through their myths, trade, and cultural practices, introduced this enigmatic seed to the world, shaping its name and early scientific understanding. The term coco de mer and the scientific name Lodoicea maldivica immortalize the Maldives’ role, despite the palm’s Seychelles origin. Historical documents, including The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (1910), affirm the Maldives’ pivotal contribution, highlighting how Maldivian traditions and trade networks brought the coco de mer from obscurity to global fascination. Today, as conservation efforts protect this endangered species, the Maldivian legacy remains a vital chapter in the coco de mer’s storied history.

The Maldivian Connection: A Gift from the Sea

Long before the coco de mer’s true origin was identified, its massive, bilobed seeds washed ashore on the beaches of the Maldives, carried eastward by Indian Ocean currents. These seeds, hollow after germination, floated vast distances from the Seychelles, appearing as mysterious objects to Maldivian islanders. Lacking knowledge of their terrestrial source, Maldivians crafted myths, believing the seeds grew on a mythical tree at the bottom of the sea, a gift from the Sea King. In the Maldives, the coco de mer was locally known as Thaavah Kaarhi, and it held significant cultural and medicinal value. The seeds were considered symbols of good fortune, and their hard shells were used in traditional medicine, particularly for sexual enhancement and as a supposed antidote to poisoning.

Maldivians were the first to trade these seeds, introducing them to the broader Indian Ocean world. By the 16th century, the coco de mer had become a prized commodity, valued for its rarity and exotic appearance. European sailors and traders encountered the seeds through Maldivian intermediaries, who collected them from their shores. The seeds’ suggestive shape fueled romantic and mystical tales, with Maldivian legends portraying them as the “forbidden fruit” associated with love and passion. This trade elevated the coco de mer’s status, with polished shells adorned with jewels becoming collectibles in European noble galleries.

The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (Volume 19, 1910) provides insight into this early connection. It notes that the coco de mer was “well-known to the natives of the Maldives,” who regarded it as a marine product due to its frequent appearance on their beaches. The journal highlights the Maldives’ role in disseminating the seed, stating that “the nuts were carried by ocean currents to the Maldives, where they were gathered and traded as objects of curiosity and value.” This document underscores the Maldivians’ role in introducing the coco de mer to global trade networks, long before its botanical origin was understood.

The Myth of the Sea Coconut and the Name “Coco de Mer”

The name “coco de mer” (French for “coconut of the sea”) directly stems from Maldivian tradition and the maritime mystery surrounding the seed. Early European explorers, encountering the seeds through Maldivian trade, adopted the local belief that they originated from an underwater tree.

This misconception persisted until 1768, when French explorer Chevalier Marion Dufresne landed in the Seychelles and identified the coco de mer as the fruit of a terrestrial palm. Prior to this discovery, the seed’s appearance in the Maldives fueled speculation, with some believing it was a sea-bean or drift seed. The Maldivian tradition of attributing the seed to a mythical underwater tree shaped early European perceptions, cementing the name coco de mer in botanical and cultural lexicon.

bThe Scientific Name: Lodoicea maldivica and Its Maldivian Roots

Lodoicea Maldivica was first recorded by Garcia de Orta in 1563 as coco das Maldivas. The scientific name Lodoicea maldivica further reflects the Maldives’ historical association with the coco de mer. The genus name Lodoicea is attributed to Philibert Commerson, who may have derived it from Lodoicus, a Latinized form of Louis, in honor of King Louis XV of France, or possibly from Laodice, a figure from Greek mythology. The specific epithet maldivica directly references the Maldives, where the seeds were first encountered and traded. This name was formalized before the 18th century, when the Seychelles were uninhabited, and the seeds’ true origin was unknown.

In 1750, Dutch botanist Georg Eberhard Rumphius studied the seed and named it Cocus maldivica, reinforcing the Maldivian connection. However, in 1801, French botanist J.J. de La Billardière proposed Lodoicea seychellarum, a name more geographically accurate to its Seychelles origin. Despite this, the earlier name Lodoicea maldivica took precedence under international botanical nomenclature conventions in 1917, prioritizing older names. Thus, the scientific name Lodoicea maldivica preserves the Maldives’ historical role, even though the palm is not native to the archipelago.

The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (1910) supports this naming history, noting that “the specific name maldivica was given due to the frequent drift of the nuts to the Maldives, where they were first known to science.” It further mentions that early botanists, unaware of the Seychelles’ palm, relied on Maldivian accounts and specimens, solidifying the name’s connection to the Maldives.

Cultural and Historical Significance in the Maldives

In Maldivian culture, the coco de mer was more than a trade item; it was a symbol of mystique and utility. The hard shells were crafted into goblets, often engraved with gold or silver, used by Indian rajahs to neutralize toxins, a belief rooted in Maldivian medicinal practices. The seeds’ rarity made them a status symbol, and their trade enriched Maldivian communities. During the era of Maldivian Sultans, embassies sent to foreign kings always included coco de mer among the gifts. Copies of missives from the Sultan of the Maldives to the Dutch and later British Governors of Ceylon mention the inclusion of coco de mer in these diplomatic offerings, highlighting its value in fostering alliances. The Maldives’ strategic position in Indian Ocean trade routes facilitated the coco de mer’s spread, introducing it to Arab, Indian, and later European markets.The Journal also alludes to the cultural significance, describing how “Maldivian islanders revered the nut as of divine origin, incorporating it into their traditional pharmacopeia.” This reverence underscores the Maldives’ role in elevating the coco de mer’s global profile, transforming it from a beachcomber’s find into a coveted artifact.

Conclusion

The coco de mer’s connection to the Maldives is a testament to the power of human curiosity and maritime exchange. Maldivians, through their myths, trade, and cultural practices, introduced this enigmatic seed to the world, shaping its name and early scientific understanding. The term coco de mer and the scientific name Lodoicea maldivica immortalize the Maldives’ role, despite the palm’s Seychelles origin. Historical documents, including The Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society (1910), affirm the Maldives’ pivotal contribution, highlighting how Maldivian traditions and trade networks brought the coco de mer from obscurity to global fascination. Today, as conservation efforts protect this endangered species, the Maldivian legacy remains a vital chapter in the coco de mer’s storied history.