Following a devastating military crackdown in their home country in 2017, tens of thousands of Rohingya refugees have been living in filthy camps in Bangladesh. On Thursday, they demonstrated and demanded to be returned to Myanmar.

The camps in southeast Bangladesh are now home to more than a million Rohingya, making them the biggest refugee population on earth.

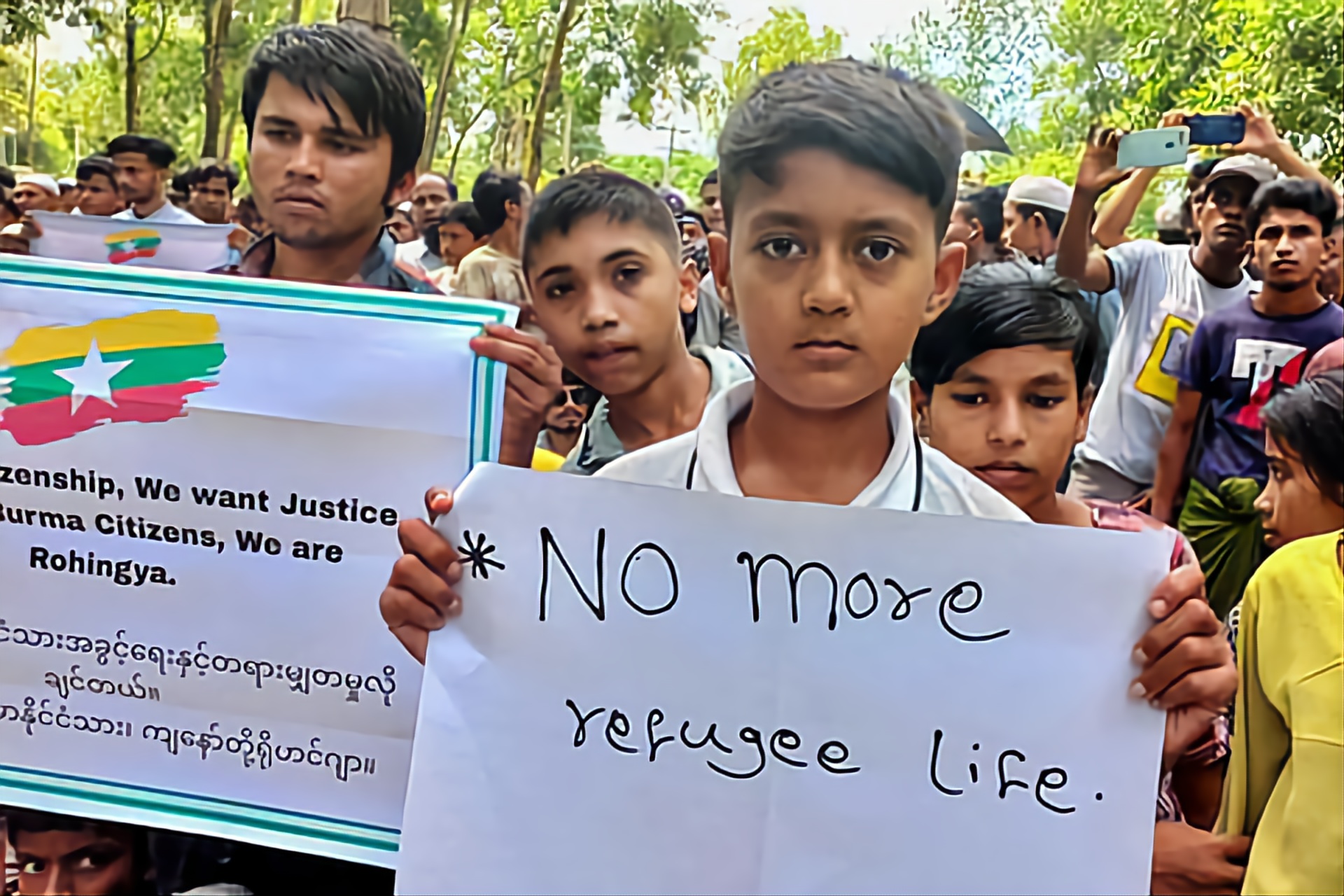

Refugees of all ages held signs and yelled slogans during Thursday's protests throughout the large camps.

“No more refugee life. No verification. No security. No interview. We want quick repatriation through UNHCR data card. We want to go back to our motherland,” the placards read.

“Let’s go back to Myanmar. Don’t try to stop repatriation.”

Rohingya community leader Mohammad Jashim said he was keen to return to Myanmar but wanted citizenship rights guaranteed.

“We are the citizens of Myanmar by birth. We want to go back home with all our rights, including citizenship, free movement, livelihood, safety, and security,” he said.

“We want the United Nations to help us to go back to our motherland. We want the world community to help us to save our rights in Myanmar,” he added.

Repatriation efforts in 2018 and 2019 were unsuccessful since the refugees hesitated at returning out of concern for their safety.

In addition, 20 Muslims from the Rohingya ethnic group declared they would not return to Myanmar to "be confined in camps" after visiting their country as part of a trial program to promote voluntary repatriation. A Bangladeshi official stated that although no date had been established, the pilot program anticipated roughly 1,100 refugees returning to Myanmar.

Every refugee has "an inalienable right" to return to their place of origin, according to the UNHCR, but such returns must also be voluntarily made.

The Rohingya have long been considered foreign intruders in Myanmar, denied citizenship, and have received little support from the military until lately.

The camps in southeast Bangladesh are now home to more than a million Rohingya, making them the biggest refugee population on earth.

Refugees of all ages held signs and yelled slogans during Thursday's protests throughout the large camps.

“No more refugee life. No verification. No security. No interview. We want quick repatriation through UNHCR data card. We want to go back to our motherland,” the placards read.

“Let’s go back to Myanmar. Don’t try to stop repatriation.”

Rohingya community leader Mohammad Jashim said he was keen to return to Myanmar but wanted citizenship rights guaranteed.

“We are the citizens of Myanmar by birth. We want to go back home with all our rights, including citizenship, free movement, livelihood, safety, and security,” he said.

“We want the United Nations to help us to go back to our motherland. We want the world community to help us to save our rights in Myanmar,” he added.

Repatriation efforts in 2018 and 2019 were unsuccessful since the refugees hesitated at returning out of concern for their safety.

In addition, 20 Muslims from the Rohingya ethnic group declared they would not return to Myanmar to "be confined in camps" after visiting their country as part of a trial program to promote voluntary repatriation. A Bangladeshi official stated that although no date had been established, the pilot program anticipated roughly 1,100 refugees returning to Myanmar.

Every refugee has "an inalienable right" to return to their place of origin, according to the UNHCR, but such returns must also be voluntarily made.

The Rohingya have long been considered foreign intruders in Myanmar, denied citizenship, and have received little support from the military until lately.