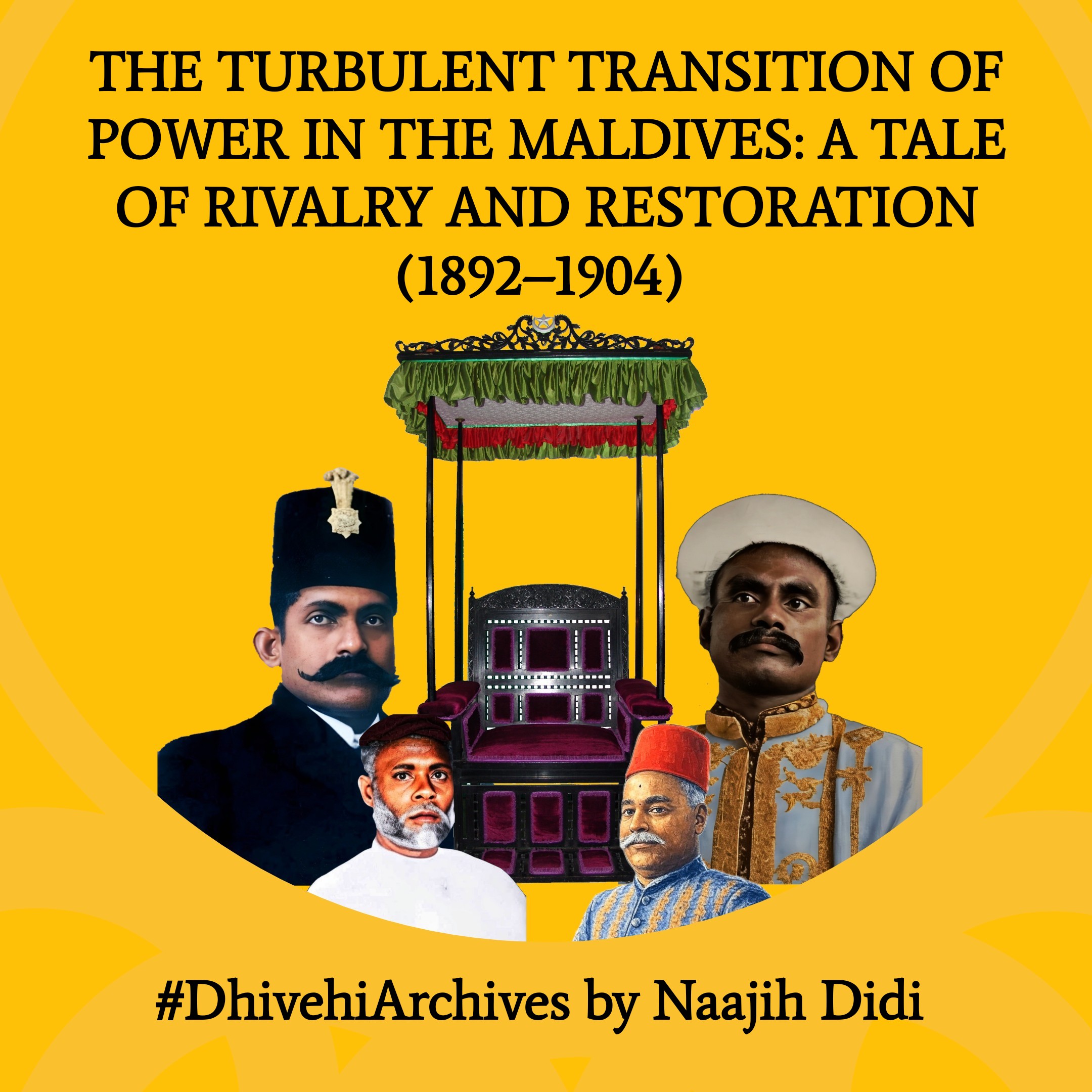

The late 19th and early 20th centuries marked a period of political upheaval in the Maldives, characterized by rapid changes in leadership, intense factional rivalries, and the struggle for legitimacy. The transition from Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III to Sultan Mohamed Imaduddeen VI, and the eventual restoration of Shamsuddeen III, as documented in H.C.P. Bell’s The Maldive Islands: Monograph on the History, Archæology, and Epigraphy, offers a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of power, custom, and colonial oversight in the Maldives. This article explores the political feud between the Athireege and Kakaage houses, the contentious successions, and the broader implications of these events for Maldivian governance.

The Death of Sultan Ibrahim Nooraddeen and the Question of Succession

The death of Sultan Ibrahim Nooraddeen on November 29, 1892, plunged the Maldives into a crisis of succession. With four minor sons and no clear successor, the Council of Ministers, led by Ibrahim Didi (Ibrahim Dhorhimeynaa Kilegefaanu) of the Athireege house, faced a delicate decision. Nooraddeen’s eldest son, aged around thirteen or fourteen, was born to Don Goma, a niece of Mohamed Didi (Mohamed Rannaban'deyri Kilegefanu) of the Kakaage house. The younger son, only eight years old, was born to Bodugalugé Didi. Despite the elder son’s seemingly stronger claim, the Council controversially chose the younger boy, crowning him Sultan Mohamed Imaduddeen V on December 8, 1892. This decision, justified by the late Sultan’s alleged wish for one of his sons to succeed him, sparked immediate discontent and set the stage for a prolonged power struggle.

The choice of the younger son was perceived as a maneuver by Ibrahim Didi and his allies to consolidate power, sidelining Mohamed Didi, a seasoned political figure and great-uncle to the elder son. Mohamed Didi, who had served as Prime Minister under three previous sultans, left the Maldives with his two brothers, Kakaagé Abdulla Didi and Kakaagé Ismail Didi, for Maliku (Minicoy) and from there protested vigorously, appealing to the Ceylon Government, the Maldives’ colonial protector, for intervention. The Ceylon Governor demanded clarification on the Maldivian law of succession, but the Council’s vague response failed to satisfy, highlighting the opaque and contested nature of royal succession in the Maldives.

The Rise and Fall of Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III

Public discontent with the appointment of the eight-year-old Imaduddeen V grew swiftly. By May 1893, a popular uprising, supported by the militia and key island inhabitants, deposed Imaduddeen V and installed his elder half-brother as Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III. This move was formalized on July 12, 1893, with Shamsuddeen III, still a minor, declaring his enthronement in a letter to Mohamed Didi, urging his return to resume the role of Prime Minister. The people’s letter accompanying this announcement emphasized their dissatisfaction with the previous regime and their belief in Shamsuddeen’s ability to govern, albeit under the regency of his cousin, Hasan Nooraddeen, a son of his father's elder brother Prince Hasan Izzuddeen (the blind Prince).

However, Shamsuddeen’s reign was short-lived. In a stunning turn of events, Regent Hasan Nooraddeen, supported by Ibrahim Didi and other ministers, seized the throne in August 1893, proclaiming himself Sultan and changing his regnal name to Mohamed Imaduddeen VI. The justification for this coup was the alleged incompetence of a “mere lad” as sultan, with claims of widespread public support for the change. Yet, the legitimacy of Imaduddeen VI’s ascension was dubious, as evidenced by the Council’s weak defense, which relied on the vague argument that both Imaduddeen VI and Shamsuddeen III were part of the same royal stock. This maneuver underscored the deep rivalry between the Athireege and Kakaage houses, with Ibrahim Didi’s support for Imaduddeen VI countering Mohamed Didi’s influence over Shamsuddeen III.

Colonial Intervention and the Legitimization of Imaduddeen VI

The British, through the Ceylon Government, were drawn into the Maldivian succession crisis due to their role as protectors of the Maldives. In 1894, Governor Sir A.E. Havelock dispatched Mr. Gerald Browne to Malé to investigate whether Imaduddeen VI’s appointment adhered to Maldivian customs and enjoyed popular support. Browne’s brief visit, marked by tact but limited scrutiny, concluded with the formal recognition of Imaduddeen VI, including the delivery of a letter of recognition and a salute to his flag. This decision, however, ignored persistent protests from Shamsuddeen III’s supporters, who continued to challenge Imaduddeen VI’s legitimacy.

Imaduddeen VI’s reign, lasting from 1893 to 1903, was marred by allegations of mismanagement, nepotism, and financial irresponsibility. His reliance on favorites, such as his brother-in-law Eggamugé Ahmed Didi, alienated key factions and fueled discontent. The Maldives’ heavy indebtedness to the Borah firm Carimjee Jafferjee & Co., amounting to over two lakhs, further strained the economy, with the government making little effort to settle these debts. By 1899, the political pendulum swung back toward Mohamed Didi, who was recalled to Malé and reinstated as Prime Minister, displacing Ibrahim Didi, who later left for Ceylon. This shift marked a temporary resurgence of Kakaage influence, but it did little to stabilize Imaduddeen VI’s increasingly precarious rule.

The Revolution of 1903 and Shamsuddeen III’s Restoration

By 1902, Imaduddeen VI’s position was untenable. His decision to leave for Mecca in 1900 and later to Egypt in 1902, ostensibly to marry an Egyptian noblewoman, left the Maldives under the regency of his half-brothers. This absence provided an opportunity for Shamsuddeen III’s supporters to mobilize. In March 1903, with Shamsuddeen having reached the age of majority, the Maldivian Ministers, led by Athireegé Abdul Majid Didi, the second son of Ibrahim Didi, declared Shamsuddeen the rightful sultan, citing his maturity and the unanimous consent of the people. This peaceful revolution, devoid of bloodshed, reflected the deep-seated frustration with Imaduddeen VI’s misrule.

The Ceylon Government, initially reluctant to revisit the succession issue, was compelled to act in response to detailed accusations of Imaduddeen VI’s maladministration. In May 1903, Lieutenant-Governor E.F. im Thurn was dispatched to Malé aboard H.M.S. Highflyer to conduct a thorough investigation. Im Thurn’s meticulous inquiry, involving testimony from a wide range of Maldivians, confirmed the overwhelming opposition to Imaduddeen VI. The people promised to provide him with financial support as a royal prince but refused to recognize him as sultan. On June 17, 1903, Governor Sir J. West Ridgeway publicly acknowledged the “rude justice” of Shamsuddeen III’s restoration, effectively endorsing the revolution.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III’s second accession in 1903 marked the beginning of a more stable reign, formalized by British recognition in January 1904. Ibrahim Didi, recalled from Colombo, resumed the role of Prime Minister and served until his death in 1925, providing continuity and effective governance. Mohamed Didi, content to retire from the forefront, accepted a ministerial role, signaling a reconciliation between the rival Athireege and Kakaage houses.

The events of 1892–1904 highlight the complexities of Maldivian succession, where custom, public sentiment, and political maneuvering intertwined. The rivalry between the Athireege and Kakaage houses, embodied by Ibrahim Didi and Mohamed Didi, shaped the power dynamics, with each faction leveraging their influence to back competing claimants. British colonial oversight, while initially hesitant, played a crucial role in legitimizing the eventual outcome, underscoring the status of Maldives under British protection.

This period also reflects broader themes of governance and legitimacy in small, tradition-bound societies navigating external influences. The restoration of Shamsuddeen III, driven by popular will and validated by colonial inquiry, demonstrates the resilience of Maldivian customs in asserting rightful leadership, even amidst internal strife and external pressures. The saga of these turbulent years remains a pivotal chapter in the Maldivian history, illustrating the delicate balance between tradition, power, and justice.

The Death of Sultan Ibrahim Nooraddeen and the Question of Succession

The death of Sultan Ibrahim Nooraddeen on November 29, 1892, plunged the Maldives into a crisis of succession. With four minor sons and no clear successor, the Council of Ministers, led by Ibrahim Didi (Ibrahim Dhorhimeynaa Kilegefaanu) of the Athireege house, faced a delicate decision. Nooraddeen’s eldest son, aged around thirteen or fourteen, was born to Don Goma, a niece of Mohamed Didi (Mohamed Rannaban'deyri Kilegefanu) of the Kakaage house. The younger son, only eight years old, was born to Bodugalugé Didi. Despite the elder son’s seemingly stronger claim, the Council controversially chose the younger boy, crowning him Sultan Mohamed Imaduddeen V on December 8, 1892. This decision, justified by the late Sultan’s alleged wish for one of his sons to succeed him, sparked immediate discontent and set the stage for a prolonged power struggle.

The choice of the younger son was perceived as a maneuver by Ibrahim Didi and his allies to consolidate power, sidelining Mohamed Didi, a seasoned political figure and great-uncle to the elder son. Mohamed Didi, who had served as Prime Minister under three previous sultans, left the Maldives with his two brothers, Kakaagé Abdulla Didi and Kakaagé Ismail Didi, for Maliku (Minicoy) and from there protested vigorously, appealing to the Ceylon Government, the Maldives’ colonial protector, for intervention. The Ceylon Governor demanded clarification on the Maldivian law of succession, but the Council’s vague response failed to satisfy, highlighting the opaque and contested nature of royal succession in the Maldives.

The Rise and Fall of Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III

Public discontent with the appointment of the eight-year-old Imaduddeen V grew swiftly. By May 1893, a popular uprising, supported by the militia and key island inhabitants, deposed Imaduddeen V and installed his elder half-brother as Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III. This move was formalized on July 12, 1893, with Shamsuddeen III, still a minor, declaring his enthronement in a letter to Mohamed Didi, urging his return to resume the role of Prime Minister. The people’s letter accompanying this announcement emphasized their dissatisfaction with the previous regime and their belief in Shamsuddeen’s ability to govern, albeit under the regency of his cousin, Hasan Nooraddeen, a son of his father's elder brother Prince Hasan Izzuddeen (the blind Prince).

However, Shamsuddeen’s reign was short-lived. In a stunning turn of events, Regent Hasan Nooraddeen, supported by Ibrahim Didi and other ministers, seized the throne in August 1893, proclaiming himself Sultan and changing his regnal name to Mohamed Imaduddeen VI. The justification for this coup was the alleged incompetence of a “mere lad” as sultan, with claims of widespread public support for the change. Yet, the legitimacy of Imaduddeen VI’s ascension was dubious, as evidenced by the Council’s weak defense, which relied on the vague argument that both Imaduddeen VI and Shamsuddeen III were part of the same royal stock. This maneuver underscored the deep rivalry between the Athireege and Kakaage houses, with Ibrahim Didi’s support for Imaduddeen VI countering Mohamed Didi’s influence over Shamsuddeen III.

Colonial Intervention and the Legitimization of Imaduddeen VI

The British, through the Ceylon Government, were drawn into the Maldivian succession crisis due to their role as protectors of the Maldives. In 1894, Governor Sir A.E. Havelock dispatched Mr. Gerald Browne to Malé to investigate whether Imaduddeen VI’s appointment adhered to Maldivian customs and enjoyed popular support. Browne’s brief visit, marked by tact but limited scrutiny, concluded with the formal recognition of Imaduddeen VI, including the delivery of a letter of recognition and a salute to his flag. This decision, however, ignored persistent protests from Shamsuddeen III’s supporters, who continued to challenge Imaduddeen VI’s legitimacy.

Imaduddeen VI’s reign, lasting from 1893 to 1903, was marred by allegations of mismanagement, nepotism, and financial irresponsibility. His reliance on favorites, such as his brother-in-law Eggamugé Ahmed Didi, alienated key factions and fueled discontent. The Maldives’ heavy indebtedness to the Borah firm Carimjee Jafferjee & Co., amounting to over two lakhs, further strained the economy, with the government making little effort to settle these debts. By 1899, the political pendulum swung back toward Mohamed Didi, who was recalled to Malé and reinstated as Prime Minister, displacing Ibrahim Didi, who later left for Ceylon. This shift marked a temporary resurgence of Kakaage influence, but it did little to stabilize Imaduddeen VI’s increasingly precarious rule.

The Revolution of 1903 and Shamsuddeen III’s Restoration

By 1902, Imaduddeen VI’s position was untenable. His decision to leave for Mecca in 1900 and later to Egypt in 1902, ostensibly to marry an Egyptian noblewoman, left the Maldives under the regency of his half-brothers. This absence provided an opportunity for Shamsuddeen III’s supporters to mobilize. In March 1903, with Shamsuddeen having reached the age of majority, the Maldivian Ministers, led by Athireegé Abdul Majid Didi, the second son of Ibrahim Didi, declared Shamsuddeen the rightful sultan, citing his maturity and the unanimous consent of the people. This peaceful revolution, devoid of bloodshed, reflected the deep-seated frustration with Imaduddeen VI’s misrule.

The Ceylon Government, initially reluctant to revisit the succession issue, was compelled to act in response to detailed accusations of Imaduddeen VI’s maladministration. In May 1903, Lieutenant-Governor E.F. im Thurn was dispatched to Malé aboard H.M.S. Highflyer to conduct a thorough investigation. Im Thurn’s meticulous inquiry, involving testimony from a wide range of Maldivians, confirmed the overwhelming opposition to Imaduddeen VI. The people promised to provide him with financial support as a royal prince but refused to recognize him as sultan. On June 17, 1903, Governor Sir J. West Ridgeway publicly acknowledged the “rude justice” of Shamsuddeen III’s restoration, effectively endorsing the revolution.

The Aftermath and Legacy

Sultan Mohamed Shamsuddeen III’s second accession in 1903 marked the beginning of a more stable reign, formalized by British recognition in January 1904. Ibrahim Didi, recalled from Colombo, resumed the role of Prime Minister and served until his death in 1925, providing continuity and effective governance. Mohamed Didi, content to retire from the forefront, accepted a ministerial role, signaling a reconciliation between the rival Athireege and Kakaage houses.

The events of 1892–1904 highlight the complexities of Maldivian succession, where custom, public sentiment, and political maneuvering intertwined. The rivalry between the Athireege and Kakaage houses, embodied by Ibrahim Didi and Mohamed Didi, shaped the power dynamics, with each faction leveraging their influence to back competing claimants. British colonial oversight, while initially hesitant, played a crucial role in legitimizing the eventual outcome, underscoring the status of Maldives under British protection.

This period also reflects broader themes of governance and legitimacy in small, tradition-bound societies navigating external influences. The restoration of Shamsuddeen III, driven by popular will and validated by colonial inquiry, demonstrates the resilience of Maldivian customs in asserting rightful leadership, even amidst internal strife and external pressures. The saga of these turbulent years remains a pivotal chapter in the Maldivian history, illustrating the delicate balance between tradition, power, and justice.